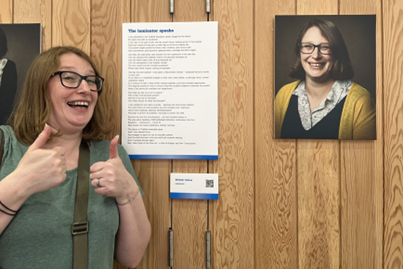

Having been introduced to the poetry library through our LIHNN network, we were fortunate enough to catch the end of the NHS exhibition marking not only its 75th year but a poetic documentation of the lived experience of its workforce throughout the Covid-19 Pandemic.

Never having had the pleasure of meeting Michelle Dutton in person before, I was introduced to her twice as her own portrait and words were among the stories on the walls – two for the price of one! Michelle

was a tremendous support for me when I first took up post in January, the go-to for all my enquiries

for Athens logins, general technical guru and someone who really made me welcome into the library

world. It was nice to put a very friendly face to all the lovely emails I had come to appreciate in those

first few weeks.

[Picture Credit - Siobhan]

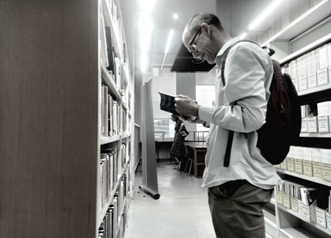

It was interesting to witness our colleagues reading these; some of us stood silently taking in the text, others were quietly mouthing the words and this difference made me wonder whether some of us were echoing our own experiences of working within the NHS throughout the pandemic.

I realised I was silently digesting the texts, as I was still teaching when words like “coronavirus” and “lockdown” were first being introduced to us. My work at that time became busier and more populated than ever as educators were expected to adapt their curricula rapidly, demand for health and wellbeing programmes was high and my classes went virtual - a stark contrast to a silent library that I can only envisage must have felt like an eerie calm in the eye of a terrifying storm.

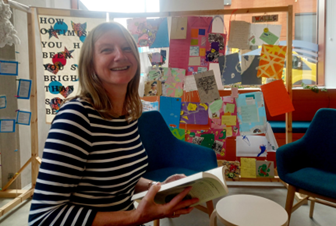

As I’m still revising my professional identify, one word stood out during this visit, that as librarians we are “activists”, ensuring equitable access to information and the democratisation of knowledge. These principles are the foundations of the poetry library, shouting out loud almost as soon as you walk through its doors. Delicate yet self-supporting and confrontational there were a collection of “zines” on the first shelves – deposited by members of the public - raw, accessible, physical; a kind of contemporary cuneiform that all of us, whether we’ve ever written verse or not, can reach.

And its users have described this library as a soft space. Soft space as defined by the American Society of Landscape Architects (2012) is the “social coding of space: space made and remade by human activity, through everyday social interactions with material space”. Danish academic Tønnes Bekker-Nielsen suggests these spaces play a key part in shaping our everyday lives and in the interests of communities, democracy, rights and freedoms, such “bottom up” spaces are vital for individual and collective wellbeing (Bekker-Nielsen 2014). Since the Danes consistently rank among the top three happiest countries in the world (Wise Voter 2023) (and their weather is even worse than ours), I think he’s onto something.

And its users have described this library as a soft space. Soft space as defined by the American Society of Landscape Architects (2012) is the “social coding of space: space made and remade by human activity, through everyday social interactions with material space”. Danish academic Tønnes Bekker-Nielsen suggests these spaces play a key part in shaping our everyday lives and in the interests of communities, democracy, rights and freedoms, such “bottom up” spaces are vital for individual and collective wellbeing (Bekker-Nielsen 2014). Since the Danes consistently rank among the top three happiest countries in the world (Wise Voter 2023) (and their weather is even worse than ours), I think he’s onto something.

The poetry library is deliciously low-tech in places, with a colourful assortment of vinyls and a record player for those who prefer to hear words spoken. It was here we learned that the oldest existing recording of a poet reading their own work dates back to 1889, when Robert Browning read an extract of his poetry to an audience of drunken Victorians. I left the library wanting to hear this inebriated 19th century crowd for myself and found it here: How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix - an extract - Poetry Archive They’re not rowdy drunks, but there’s a rather enthusiastic “hooray” at the end.

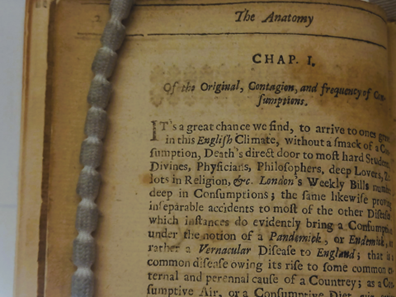

Breathing in that oddly pleasing scent of old books, the second half of the day was spent poring over an historic collection of rare texts and medical ephemera; a history of healthcare innovation in a score of objects. Here, in the book Morbus anglicus : or The anatomy of consumptions […] dated 1672, physician Gideon Harvey was the first to document the term “Pandemick”. Printed 348 years before Covid, Harvey refers to the Consumption as a malignant disease that “haunt a Country” and, “...to which are added some brief discourses”, he hastened to say in his lengthy title, “of melancholy, madness, and distraction occasioned by love.” Harvey could never have envisaged when he penned such an interesting title how those words sound like a Haiku that pretty well captures our lived experience of 2020.

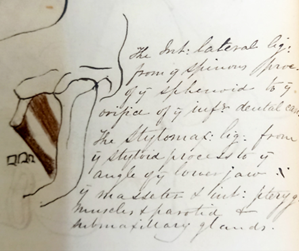

The carefully annotated, handcrafted illustrations within these books remind us that the study and practice of medicine was both an art and a science. And these texts were living, working documents - the earliest point of care tool.

Jotted down in notes and sketched from observation, these early records of knowledge, the first textbooks and clinical data assets, mirrored a rudimentary blend of Art and Science that would not have agreed with Professor Sir John Charnley. Charnley was a Northwest Orthopaedic Surgeon who performed the first total hip replacement in 1962 in his clinic at Wrightington Hospital. In his book, The Closed Treatment of Common Fractures, published in 1950, he sought to demonstrate “that far from being a crude and uncertain art, the manipulative treatment of fractures can be resolved into something of a science." The Art, and all its intricate representations of the human form, was shelved. Technology was now driving healthcare forwards; here is a Thompson Hip Prosthesis, circa 1950s, made from Vitallium alloy; a corrosive-resistant material, introduced for prosthetic use in 1936.

Concerned about infection control, Charnley worked tirelessly to minimise risk to patients undergoing this procedure.

Concerned about infection control, Charnley worked tirelessly to minimise risk to patients undergoing this procedure.

But his innovations were also evident in his approach to knowledge and information. The year before he performed this surgery, Charnley noted, “...a tendency to imagine that...research can only come out of a laboratory,” and argued for greater clinical reasoning. “Contributions from the pure act of contemplating clinical facts” he concluded, “has ended with the great clinicians of the past.” He called for medical students and emerging clinicians to “foster the habit of making clinical observations and questioning accepted beliefs”. For him, the science of medical practice was discursive; in his words we can hear echoes of peer reviewing, critical appraisal and evidence-based practice. People like Sir Charnley, and the centuries of botanists, anatomical illustrators and philosophers who have gone before him, laid the foundations of the NHS we know as it marks its 75th year.

Efforts to reduce infection risk have raised issues of sustainability in the use of disposable, often plastic, medical supplies. With our NHS supply chain accounting for 66% of the overall carbon emissions , it was interesting to see this vaccination kit, circa 1950s, when it was commonly found in many physicians’ bags, and probably reused countless times.

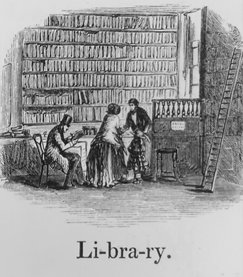

As I mentioned earlier, I’m still shaping my professional identity, but this 1857 Illustrated vocabulary for the use of the deaf and dumb, by T.J. Watson, did little to alleviate any feelings akin to imposter syndrome I may have, and I think the Health & Safety Executive might have a word or two to say about that rather high shelving:

Our last reflection of the day was one of equality, diversity and inclusivity. Thankfully to be Deaf is now seen as culturally diverse and its language is celebrated by both hearing and Deaf communities alike, and best summarised in this two-minute poem in British Sign Language by Richard Carter:

BSL poem "Identities" by Richard Carter - YouTube

Andreya B. Platia

Trainee Clinical Librarian

Library & Knowledge Services

University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS Foundation Trust

References

American Society of Landscape Architects (2012) Hard Space, Soft Space, and Architectures

of Appropriation. Retrieved from Hard Space, Soft Space, and Architectures of Appropriation

| LA CES™ (asla.org)

Bekker-Nielsen (2014) Ch. 7 ‘Hard and Soft Spaces in the Ancient World’ in Features of

Common Sense Geography, Geus, K. & Thiering, M. (Eds.) Zürich: Lit Verlag. GmbH & Co.

131-146. Retrieved from

https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=XvXYAwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA131&dq=t

he+psychological+importance+of+soft+space&ots=m3065asODv&sig=p40gRzGfO2r_l9dS41X

ezAO08BU#v=onepage&q=the%20psychological%20importance%20of%20soft%20space&f=f

alse

Wise Voter (2023) ‘Happiest Countries in the World’. Retrieved from

https://wisevoter.com/country-rankings/happiest-countries-in-theworld/#:~:text=Finland%20is%20the%20happiest%20country%20in%20the%20world%2C%2

0with%20a,a%20happiness%20index%20of%207.56.