If you’ve ever been to the Libraries and Information Literacy (LILAC) conference, or any other library conference for that matter, you’ll know just how unsettling it can be to clock the same people you saw presenting deep pedagogical theories on the practice of teaching in the afternoon, now sporting a cocktail dress at the evening’s gala dinner. Yet we all appreciate that there’s a business and a casual side to everyone, and not just in the fashion department.

‘Knowledge mobilisation’ is all about meeting people where they are on their learning journey, but how do we know if they’re striding boldly down the information superhighway in their patent-leather brogues or just chilling out on the couch of knowledge apathy in a pair of comfy slippers?

Kirsty Thomson, the academic support and liaison librarian at Edinburgh’s Heriot-Watt University, had been pondering this problem. Training students to summarise and choose keywords for journal articles proved challenging. Every article should tell a story capable of summary, but often methodologies and mathematics get in the way. It didn’t fill her students with confidence to not understand what the articles meant, even if that’s more the fault of the author than the reader.

Storytelling is (or at least should be) an instinct, whether it’s that strategic presentation in the boardroom, or the trashy novel we’re reading in the bedroom, so Kirsty figured if she could tap into our instinct to enjoy a good story, she’d be able to apply it to her teaching.

But at what point are we most receptive to a good story? Probably not with that boardroom report or, unless we’re very easy to please, the trashy novel either. For true immersion, it seems we need to be facing the big screen with at least our hand in the popcorn bucket. Despite the pandemic, cinemas have bounced back pretty quickly and subscriptions to streaming services skyrocketed during that time. It seems we can’t get enough of the silver screen.

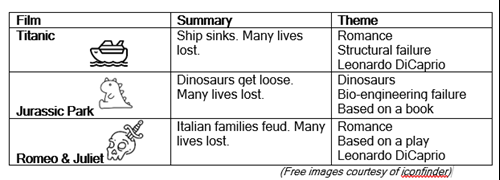

Kirsty selected three popular films from the 1990’s for her cinematic experiment: ‘Titanic’, ‘Jurassic Park’ and ‘Romeo & Juliet’. The advantage of using these three films was that they were popular, and most people had a good idea of the plot. Her plan was to use the films as a stand-in for journal articles, teaching the principle of article summary and keywords through the accessible medium of film. Once given a table to complete, she split her students into small groups to agree on a summary and a series of keywords.

The films’ themes are likely to be interpreted in different ways depending on educational background. For example, ‘structural’ and ‘bio-engineering’ failures were highlighted by Kirsty’s engineering students. However, it’s clear there are potential overlaps between the films, mirroring how journal articles also have overlapping elements. This helps students appreciate that there may be similarities and differences between related articles from which they can draw conclusions.

Kirsty was even able to draw more advanced conclusions comparing films to articles with some groups. For example:

- Jurassic Park spawned a lot of sequels. Could it be seen as a ‘seed paper’?

- Would Leonardo DiCaprio be seen as a key ‘author’ in the field?

- In ‘Titanic’ the plank of wood one character survives by laying on might have accommodated both characters with appropriate persistence and technique – does this show the ‘research’ of that paper (the film plot) was flawed?

- Jurassic Park ended badly for humans; not so for dinosaurs. A different interpretation of the same results depending on the audience?

- Romeo and Juliet would be improved by dinosaurs: discuss. Is there evidence for this or are we just being silly? (Probably the latter). An unexplored area for future research?

Any films can be used for this exercise, assuming they have some overlapping themes and are sufficiently popular for everyone to know the plot. It is also important to emphasise we’re using films are metaphors for journal articles to help demystify the synthesising and summarising process, rather than running a crash course in film criticism!

I believe it is entirely possible to transfer this knowledge into a health library setting, not only for medical students but also nurses struggling to find research to confirm their evidence-based practice during revalidation, and for junior doctors searching for ways to link their previous experiences in academia with the practicalities of a hectic hospital environment.

This session has the advantage of being novel. Just like memorable movies, the ‘plot’ of a memorable training session will elicit a stronger recall of learning. All the same, I wouldn’t recommend investing in a popcorn machine for the library just yet.

Daniel Park

Assistant Librarian

Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust